For Every Action, an Equal and Opposite Reaction

As safety net programs shrink and incarceration ramps up, we must come together to protect each other

One of the difficult things about facing impending cuts to social safety net programs like Medicaid, SNAP, subsidized housing, and childcare, is understanding that these cuts have nothing to do with cost saving. Instead, far greater amounts of money are being poured into incarceration. As Val Weisler notes in her article about childcare organizing in Wisconsin, the state spends $1 million annually on the incarceration of youth. This number vastly outstrips spending on early childhood education, community programs, or mental healthcare in Wisconsin, despite evidence that these early supportive systems greatly reduce adolescent contact with the justice system.

Likewise, the cost of incarcerating people living on the streets costs taxpayers substantially more than simply providing housing. However, in her op-ed about proposed changes to subsidized government housing through HUD, Safety Net Fellow Bobbi Dempsey writes about the ways that access to affordable housing may soon become even more difficult. As it is, lists for public housing or housing vouchers through HUD can involve a wait of up to ten years in many communities across the U.S., but limiting people to two years of subsidized HUD housing will result in putting many people back on the street before they’ve had a chance to get ahead.

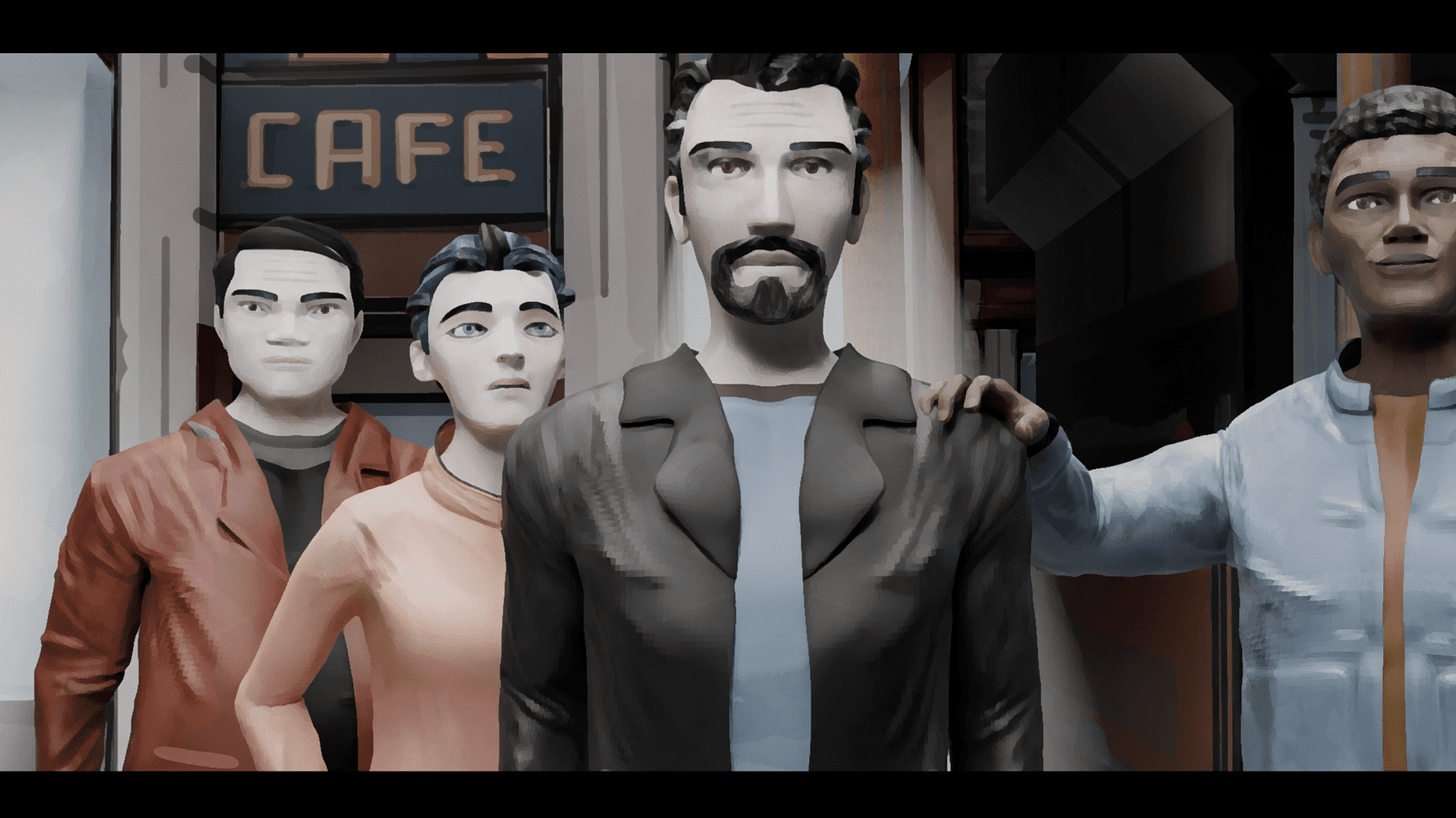

On July 24, Donald Trump signed an Executive Order aimed at further criminalizing homelessness. The order encourages states to incarcerate or institutionalize people living on the streets—a move that many experts say will only exacerbate the problem. How do we respond when an already patchy social safety net is reduced to shreds? It’s a tough fight ahead, but as ChangeWire alumnus Miguel Rueda reveals in his animated video, we all have a part to play and skills we can contribute. Continuing to organize for access to affordable childcare, housing, food, and healthcare is the way we can continue to honor our communities and the dignity and rights of everyone.

Beyond the Byline with Bobbi Dempsey

EW: How did housing instability affect you and your family when you were growing up?

There was no sense of stability or security. We never felt like we really had a “home.” If my mother did manage to pay the rent, there was no money left for anything else for the rest of the month. But most of the time, she would fall behind. We were evicted numerous times. We could never establish any sort of community or support system because we never stayed in one place long enough to make connections. It was also very challenging for me academically because I was constantly bouncing from one school to another. Up until high school, I never went a single school year in which I remained at the same school for the entire year.

EW: Did your family ever live in public housing or have access to a HUD voucher when you were growing up?

We never lived in public housing or had a HUD voucher, mostly because we were never able to remain in one city/area long enough to get off the wait list. If we’d had access to this kind of housing support it would have made a huge difference, taking a big weight off our shoulders. Financially, it would have given us a little breathing room to focus on other important expenses like food and medical care. Emotionally, it would have allowed us to have a sense of belonging and security.

EW: Based on your personal experiences, what domino effect does housing instability have on other aspects of life and how does affordable housing help alleviate those stresses?

When you are constantly worried about whether you will have a place to live, it’s almost impossible to think about anything else. It’s difficult to find or keep a job if you don’t have an address or stable housing. If you do find a place to live, you typically must come up with a significant amount of money all at once – for the security deposit, first month’s rent, etc. That means you may be forced to use money that you now won’t have for food or other expenses, meaning you’ll fall behind in other areas. Moving often is especially disruptive for children, since they may have to switch schools frequently. If you are constantly relocating, you never really get the chance to make connections with other people/families that could provide a support system.

EW: What do you anticipate would be the outcome of a two-year minimum on HUD assistance—and what would you like to see implemented instead?

Imposing a relatively short time limit like this would mean that people would have the rug pulled out from under them just when they may be able to get their head above water financially. This housing assistance gives families a little relief in their monthly budget that lets them focus on paying other bills. This will lead to more people who are unhoused or experiencing housing instability. It will also negatively impact landlords, who will have to continuously look for new tenants. I would like to see more investment in affordable housing options. It would also be helpful to have more programs to assist families with the upfront costs involved in getting a (rental) home, as this is often a huge hurdle that leads to housing insecurity.

EW: How does housing security for the most vulnerable help those families—and all of society?

Housing security allows vulnerable families to become a more active and established part of the community, allowing them to make connections with their neighbors. It also gives families the financial breathing room to let them stay on top of their other bills and perhaps even build up some savings. And I think everyone – the community and society as a whole – benefits when vulnerable families’ most basic needs are met, making it more likely that they can work, volunteer, fulfill family caregiver roles, and otherwise become productive members of the community.

Editor’s Picks

Childcare expert and ChangeWire Fellow Val Weisler writes about the childcare crisis in Wisconsin brought about by a budget that cuts childcare funding and deregulates care across the state. Advocates with Wisconsin Early Childhood Action Needed (WECAN) and their partners are calling for the state legislature to take action before the domino effect of vanishing childcare options negatively impacts the health and safety of young children and their parents’ ability to work.

ChangeWire Gabb Schivone’s poem “Luck” captures the random variables that divide those with means or housing from those without. The poem offers a window into what it’s like to live on the streets or to be seen as “less than” and asks readers to consider how citizenship, being born in the right family or right side of town, or access to options can drastically change what is possible.

ICYMI

In this original animation, former ChangeWire Fellow Miguel Rueda shares the common story of a person who wants to make change but questions his capacity, courage, and knowledge. The advice he receives is advice we all need to hear on a regular basis as we continue to figure out how to use our talents and strengths in a way that leads to a society that values equity, justice, and a social safety net for everyone.

Alumni Corner

ChangeWire alumna Sa’iyda Shabazz joined No One is Going to Save Us podcast host Gloria Riviera for an episode called “What it Really Means to Not Have Childcare.” In the episode, Shabazz recounts her pregnancy, struggles with balancing work and caring for her son as a single mom, and the real need for a social safety net that supports all families.